In 1981, Salman Rushdie released his second novel, Midnight’s Children, for which he won the Booker Prize for the best original full-length novel of the year. His fourth novel, Their Satanic Verses, was a Booker Prize finalist and won the 1988 Whitbread Award for novel of the year. His book caused Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran to issue a fatwa against him and sparked violence across the globe, including an assassination attempt on Rushdie. For his work, he has been appointed Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France, knighted by Queen Elizabeth II, and rated one of the best modern authors.

Last year, Rushdie announced his belief that television drama has replaced literature in modern culture. Though still dabbling in prose, he is also in the process of writing a science fiction television series and has sold a screenplay for a film adaptation of Midnight’s Children.

There have been great authors over time who have tried their hands in Hollywood (William Faulkner, Ray Bradbury, etc.), but it’s difficult to think of anyone else who effectively resigned themselves from the medium for which they became globally relevant to work in show business. Rushdie’s actions are indicative of a gradual phasing-out of literature in our culture in favor of other mediums.

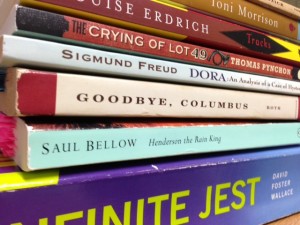

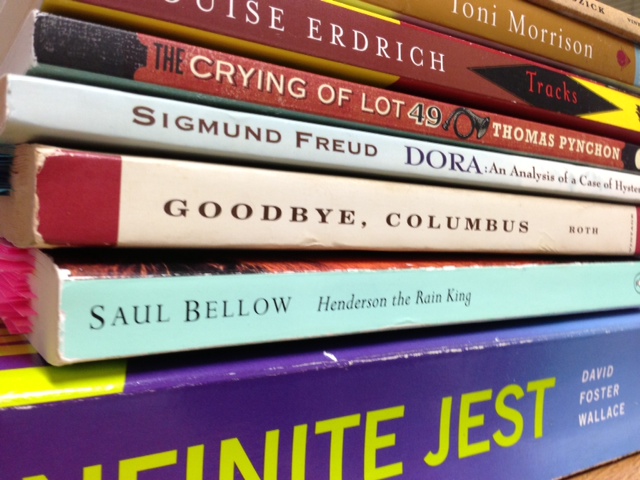

Gone are the days when a recently-released book became an instant must-read for any self-respecting adult. In the past twenty or so years, television drama has grown leaps and bounds in its depth, quality, and cultural relevance. Shows like Mad Men, The West Wing, or The Wire are able to introduce characters and themes as complex and relevant as any explored in the great American novels, while at the same time managing to be similarly impactful on large audiences, if not more so. Whereas past generations looked to F. Scott Fitzgerald or Thomas Pynchon or David Foster Wallace to explain and explore the nation’s collective consciousness, modern audiences turn to Nucky Thompson and Walter White and Tony Soprano.

The reasons for this are easily explained–TV is more accessible and more easily disseminated to a large number of people. It takes an hour to consume a show but days or weeks to finish a book. But what’s interesting is that as time goes on, our favorite shows take on more and more novelistic qualities. In a think-piece for the A.V. Club, Ryan McGee examined how our favorite shows have ceased to air self-contained, episodic stories that carry over little from week to week. Instead, each episode has become an installment in a larger narrative, a new chapter in an overarching novel, if you will. There is a manner of universe-building and character arcs traced over many seasons that reflect a Dickens-like quality, and the trend is only growing. It might be that declines in reading are occurring because other art forms are stepping in and fulfilling the literary qualities.

On the big screen, films are taking on literary qualities as well simply because of the growing number of book-to-film adaptations. Last year, six of the nine nominees for the Best Picture Oscar and four of the top ten highest grossing films were adapted from books. Despite the new wave of voices sounding the death knell for the film industry, the medium, along with others, has unmistakably replaced literature in the cultural canon.

By no means is this phenomenon limited to television and film. An increasingly popular trend in the music industry is to introduce the album as a story, with each song progressing the narrative or introducing a different character. Kendrick Lamar’s acclaimed good kid, m.A.A.d. city is the most recent, but even albums like Green Day’s American Idiot or The Decemberists’ The Hazards of Love use a similar format. In the case of Lamar, each song describes a different event in a single Compton day, tied together by skits and narration at the end of each. The technique has a way of making the music more personal and more emotionally affecting than a collection of disparate songs. By using narrative structures more and more, artists are in a sense filling the gap for compelling plots and characters that their audiences no longer get from reading.

What’s difficult is determining what the effect of this “new literature” might be. There is a surplus of statistics suggesting that rates of recreational reading have gone down, but is this necessarily a bad thing? Is reading inherently better or more valuable than watching? If one of the most important facets of literature’s past popularity was providing a national cultural touchstone, that role has easily shifted to our favorite shows and movies. This is not to say that literature is an obsolete or useless art form, but simply one that would inevitably lose popularity in the digital age. Rare is the novel not catering to young adults or suburban housewives that breaks into the mainstream–you won’t find many future English class favorites on today’s best seller shelves. The fact is inescapable, but is it necessarily for the worse? Or might it not even matter?

What rubbish. Salman Rushdie is involved in a TV series and then determines that TV has made the novel all but irrelevant. The article then goes on to mention Mad Men and The Wire as shows that are being watched rather than the reading of novels. Sorry, but The Wire had a incredibly small audience and while Mad Men is critically acclaimed its audience is not all that great either. The writer goes on to say there are no “must read” novels being released. What about the Harry Potter series, The Hunger Games and, (I cringe) Fifty Shades of Grey? TV scripts are now far better written than most movie scripts, the reason for the rise of the quality of TV but television viewing is no threat to the reading of novels.

Hi Barry, thank you for reading. In my opinion, The Wire, while little watched in its time, has come to be the golden standard in the new age of television drama. Many critics consider it the best American show of all time, others refer to it as the new “Great American Novel.” Mad Men, on the other hand, draws pretty big ratings – 3.5 million viewers for last season’s premiere and an average of 2.6 million throughout the season. Regardless of viewership, the point I was trying to make that in a random group of people, there are many more eager to talk about shows like Mad Men or Breaking Bad than the more critically acclaimed adult novels. While young adult fare like the Hunger Games series is still popular, I see a decreasing popularity of the more serious and critically acclaimed adult books. Take, for example, the three novels in consideration for last year’s Pulitzer Prize for fiction: David Foster Wallace’s ‘The Pale King,’ Denis Johnson’s ‘Train Dreams,’ and Karen Russell’s ‘Swamplandia.’ Maybe it’s just the college atmosphere I’m a part of, but I think you’d be hard pressed to find people who have read and are eager to discuss these books like they can talk about shows like Game of Thrones or The Walking Dead. I, too, lament the lack of interest in good literature, but I think its phasing-out in our culture is an unavoidable trend.

Rushdie’s also not unknown to toot his own horn–he consistently praises the english writings of modern Indian writers, and goes as far to suggest that hindi/urdu texts are less important. While it’s certainly becoming more trendy to adapt novels into film/tv scripts, to say that contemporary culture is phasing out literature is a stretch when the film industry today is so dependent on the modern novel. Film/television today are just elevated to the same standard of critique employed for literature.

Very good point about the elevated level of critique, but might it be the case that by adapting most moderately successful books to TV and film, that just strengthens the latter two while weakening the former? I think that the adapted series/films receive much more attention than the source material they are based on.