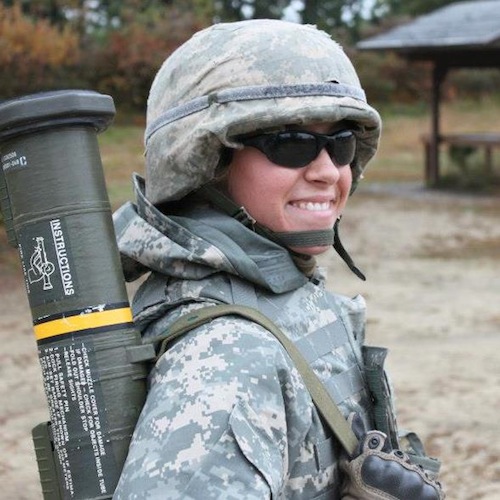

Kayleigh Andreason, blonde and blue-eyed in a sweet grey and white cardigan, spins her laptop around and points to her Facebook profile picture. She is barely recognizable, looking over her shoulder at the camera under an advanced combat helmet, flac jacket, and dark sunglasses, save for a brilliant white smile that she flashes again now. A massive cylinder of grey metal rests against her shoulder.”That is a live AT4,” she says with audible excitement. “That means it goes ‘boom.'” She pulls up a YouTube demonstration of the weapon; a resounding boom explodes out of the laptop’s speakers, causing a barely perceptible pause in the hum of patrons in the Starbucks in which she sits.

Andreason, 21, a senior in BU’s ROTC program, represents a group of women who just received some very exciting news. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta announced on January 23 that the U.S. military’s long-standing ban on women in direct combat roles would be lifted, thus allowing female soldiers to enter into positions in infantry, armor, cavalry, and special ops branches–positions they never could have filled before. The lifting of the ban will open up over 280,000 infantry jobs for interested women (NYTimes.com).

Critics of Panetta’s decision have cited inferior female physical capability, changes in team dynamics in the field, and a diffusion of personnel away from non-combat positions as reasons against the change. Whether these criticisms are valid concerns is impossible to say for sure, but based on women’s current roles in combat, the change might prove to be less drastic than asserted by its detractors.

Despite the official ban on women in direct combat, women have been in combat positions as long as they’ve been in the military, working in positions of “combat support.” These roles, though they are not technically on the front lines, involve situations as dangerous as those termed “direct combat”–for example, military policing, piloting, intelligence missions, frontline-attached missions, transporting and defusing explosives, long-range reconnaissance missions, and technological support, among others. Especially in today’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, where there exists an insurgent population, front lines are not well-defined, and the tasks required of female soldiers in combat support are often as dangerous as those “on the front line,” though they have not been recognized as such. Over 130 female American soldiers have been killed in the wars, and over 800 have been wounded (NYTimes).

What the ban has meant for female soldiers is a lack of recognition for their work that restricts career opportunities and leads to misunderstanding of women’s roles in the military– for example, it is nearly impossible to reach the rank of general without combat experience. Several women either well into or past their military careers have come forward to express that they have felt limited by the ban (See the NYTimes article “For 3 Women, Combat Option Came a Bit Late,” for examples).

Even more seriously, many women attached to front line combat have returned to the home front with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and, though women are statistically more likely to come forward about experiencing PTSD, many of those women have encountered doubt and a lack of support from peers and even medical professionals who doubt the severity of their trauma because they were not technically “in combat.” This is especially challenging in a military context across genders, as soldiers are often trained to believe that sickness is weakness (see Time Magazine’s article on soldier suicides).Women, however, are continually forced to prove, again and again, their veteran status.

But for women like Kayleigh Andreason, who was a tri-varsity athlete in high school and now plays ice hockey in what little spare time she has in between her ROTC duties and a demanding human physiology major, a world of opportunity has opened up. Andreason, who first saw Panetta’s announcement on her Facebook mini-feed, joined ROTC in her sophomore year and completed the rigorous Leadership and Development Assessment Course (LDAC) last summer. She requested her top choices for branches (military police, ordinance EOD, and field artillery and transport) in September. For those unfamiliar with ROTC processes, seniors in the program request their branches at the beginning of senior year. After graduation, Kayleigh will either attend a Basic Officer Leadership Course (BOLC), work as a tactical evaluator at LDAC, or travel until she can complete her BOLC, which could take up to a year. She will have the opportunity to switch into a combat position once she reaches the rank of First Lieutenant Promotable, after which she will be able to re-class. Kayleigh hopes to be in combat by 2016.

That being said, not all women in the military want to enter into combat. For Sarah Gloyn, 19, a sophomore in ROTC and journalism major in COM, the military was never about combat. “We’re training to be leaders,” she says.”I think that the news is great for women who want to go into combat, but I personally wouldn’t want to.” Gloyn says of the other women in her ROTC group, of which there is a substantial population (there are four women in Gloyn’s squad of ten, and women make up 14% of the U.S. military’s 1.4 million personnel), few if any had aspirations to go into combat to begin with. Those who did were on the track to fulfill roles that would essentially place them into combat roles besides, casting into doubt whether the change will actually change the diffusion of jobs across gender lines.

As far as physical capability goes, Andreason believes that the distinction between “teeth” and “tails” (that is, those at the front line and the complex supporting system keeping the operation in balance) is “a personal one, not a gender-specific one.” In ROTC, according to physical training standards (which test the number of pushups and sit-ups done in two minutes as well as a two-mile run), standards differ for men and women. For example, men must complete a minimum of 42 pushups, the same as the maximum for women. Every additional rep above the maximum earns additional points. Andreason has endeavored to match or exceed her male peers, although she prefers that her statistics remain private. “Women who want to go into combat should be able to at least match male standards,” she says. The tasks of an infantry soldier are indeed arduous, including carrying packs weighing up to 150 pounds, but as Andreason shows, capability is not necessarily determined by gender, but rather by actual strength and stamina.

Although lifting the ban on women in combat will ensure equality between men and women in terms of credit and opportunity, it is important to remember the essential and unique role of women, specifically women, in combat. Especially in a military context, wherein masculinity is heavily emphasized from training to the field, femininity does often plays a key role. Some of the duties that women in combat have and will continue to play are, in fact, impossible for men to perform. In an insurgent war environment, which entails the winning of hearts and minds, soldiers often work hand-in-hand with citizens to determine the circumstances of insurgents, their weaponry and position, etc. For example, female soldiers play a vital role if strip searches to look for concealed weapons are conducted. In Iraq and Afghanistan, where a man performing a strip search on a woman would mean destroying her honor, it is not preferable but essential that a female soldier perform the task.

The military is expected to be fully integrated by 2016. For current female freshmen in ROTC, this means that they will be able to enter into combat if they so choose once they graduate and complete BOLC. “Now, that’s really exciting,” says Andreason.