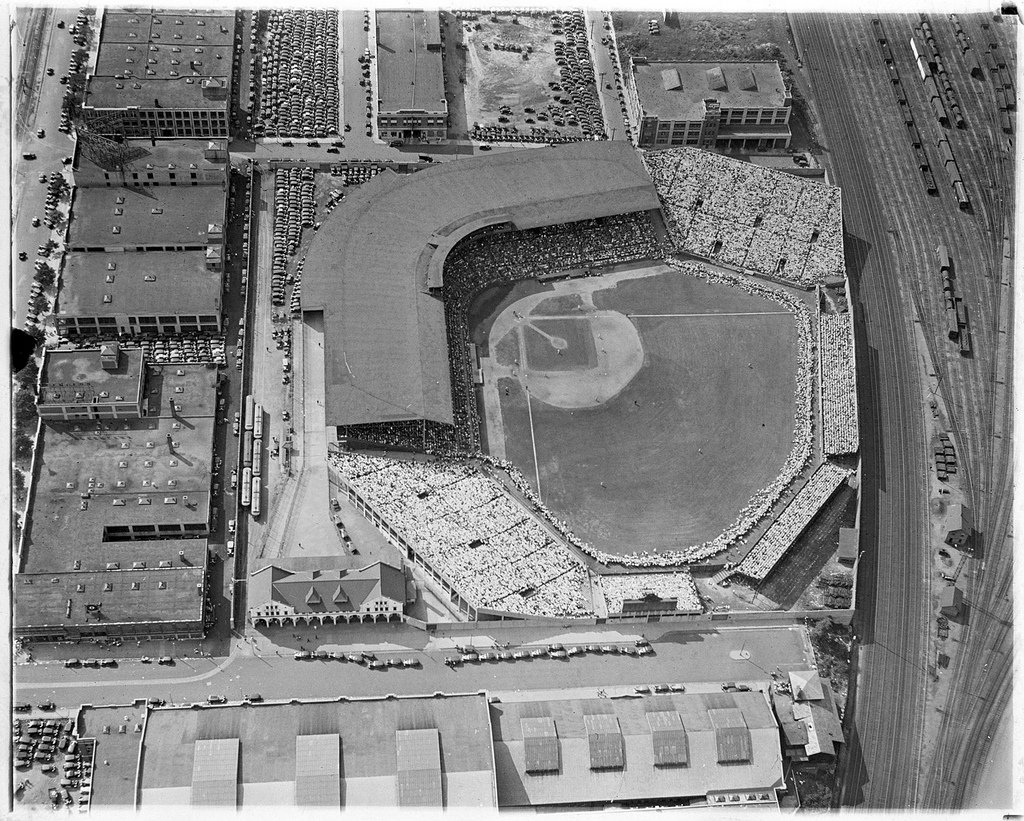

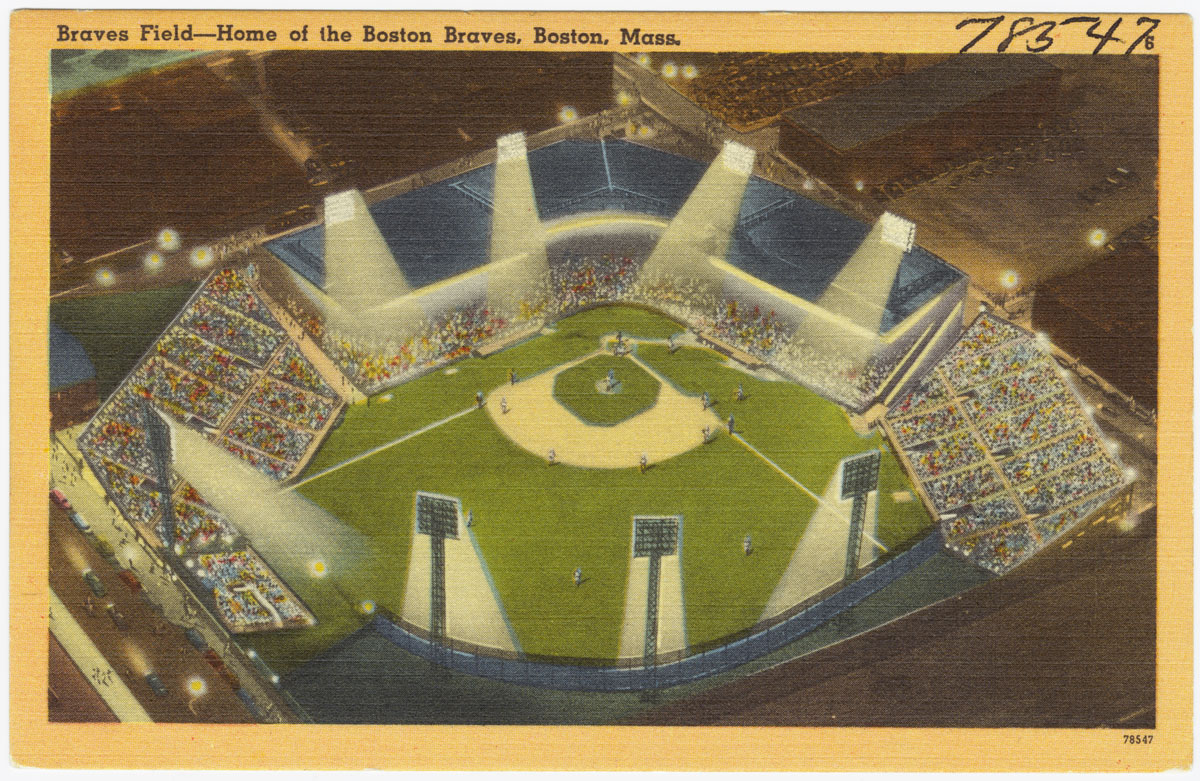

Boston University did not rise out of the Charles River. It is a heterogeneous hodgepodge of spur of the moment decisions. Although easy to take for granted, the layout of campus is the result of a century of influence. One area, West Campus, owes much of its identity to Boston’s past. Today, West Campus is BU’s athletic core. It holds many gymnasiums and playing fields—it even has a statue to Harry Agganis, our “Golden Greek.” This athletic character was inherited from the history of its construction. West Campus is literally built on the foundation of one of Boston’s most famous ballparks, Braves Field.

Although much of the park was razed when BU purchased the property in 1953, pieces of the old stadium still exist. Nickerson Field, built over the old baseball diamond, is sunk 18 feet below street level–at one time, this let baseball fans see more of the game. One of the steel-and-concrete stands, well, stands just as they did when they were build in 1915. The BUPD headquarters fills out the Braves’s old ticket and administration building. The orientation of the three dormitories maps to the construction of the original grandstands. Actually, a surprising amount of the original structure remains today, over a century later.

Braves Field was the pet project of James E. Gaffney, a New York construction company owner who purchased Boston’s National League baseball team in 1911. Playing games at their South End grounds, the Braves were limited by the small park and its wooden grandstand. Two years later, Gaffney announced on November 21, 1913, that he would construct a new steel and concrete grandstand that could seat 27,000 fans “at a cost of upward of $375,000.”1 Although Gaffney said the new park would be built by the Fourth of July, it wasn’t until December 4, 1914, that he announced the site for the new park.

Gaffney found a large piece of land on what was then the outskirts of the city; it was bounded north by the Boston and Albany Railroad, south by Commonwealth Avenue to the south, east by Pleasant Street (later Gaffney Street, now Harry Agganis Way), and west by Babcock Street. Across the street was the new Boston Armory, which would later be replaced by Agganis Arena. The lot was huge, “having an area of 593,718 square feet,” more than enough space “to build the roomiest ball park on.”2 Its location on Commonwealth Avenue was important—Gaffney expected the streetcar to help bring a huge attendance, going so far as to build a station right under the stands—and he built commercial space along Commonwealth.

Three months later, the land was purchased for $100,0003 and Gaffney was ready to begin building. Gaffney owned the property under the Commonwealth Realty Trust and awarded his construction contract to, unsurprisingly, the James E. Gaffney Construction Company. The building began in March of 1915, with an updated capacity of 45,000 people, making it the biggest grandstand in the country at that time.4 The park was expected to be built before September 1, and indeed it was: the Braves won their first home game on August 18, 1915. A few months later, Gaffney sold the team off to Percy Haughton for a rumored price of $500,000. When asked about the surprise sale, Gaffney remarked, “[W]hen I discovered I could secure a price…that would net me a substantial profit, I could not, as a business man, turn down the proposition.”5

Although he left town, Gaffney’s field remained. Built with steel and concrete, Braves Field was ahead of its time. But its huge infield and orientation towards “dead ball” play–at the time, baseball was still a pitcher’s game6— quickly dated it. After Babe Ruth ushered in the modern “live ball” era of home runs, audiences didn’t want anything but sluggers who could hit balls out of the park. To the dismay of the Braves’ owners, audiences dwindled since the stadium resisted home runs. The outfield couldn’t shrink, either: the hulking concrete stands could not be moved any closer.

Into the twenties and thirties, the Braves floundered, losing games and fans. In 1935, the president of the team, Judge Emil Fuchs, sold the last-place team for a $100,00 loss.7 The team’s fortunes picked up again in the late 40s, leading them to the World Series in 1948. Riding high, the next year the team purchased their stadium outright from Gaffney’s Commonwealth Realty Trust (Gaffney had sold the team, but not the land) with plans to expand seating. But their luck ran out quick:

While the Braves drew more than 1.45 million fans in 1948, the glory days of that season reversed themselves within four short years, as the Braves sunk to seventh place and attendance slid back down to alarmingly dismal but nonetheless familiar levels.8

By 1952, the Braves were heavily in debt. By 1953, plans were made to sell the whole franchise to Milwaukee in March. Braves Field, overgrown with weeds, was sold in July to an expanding Boston University.9 BU’s purchase of Braves Field was prescient. Weeks later, BU’s Nickerson Field in Weston, MA would be taken under eminent domain by the Massachucetts Turnpike Authority.10 The Field was turned into a highway interchange and all of BU’s athletics moved to the former home of the Braves, most of which BU dismantled.

Braves Field was purchased under the authority of Boston University’s President Case. It was the first expense in his multi-million dollar campaign throughout the 50s and 60s to unify Boston University on its Charles River Campus. The initial purchase of Braves Field focused the development of the rest of West Campus. Many of the grandstands were torn down, and in their place the West Campus tower dormitories and the Case Gymnasium were built. West became the center of campus athletics, and later the Tennis and Track Center, softball fields, and especially the student fitness center settled nearby. Most recently, a new field was constructed across Babcock Street just last year. The legacy of Braves Field has shaped the growth of Boston University’s campus and the lives of its students. The story of its founding is not arbitrary historical trivia—it is essential to understanding the present state of our campus and planning for our future.

- “GRANDSTAND TO COST $375,000: New One for Boston National Grounds.” Boston Daily Globe. Nov 22, 1913. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Boston Globe (1872-1982). Pg. 9. ?

- “BOSTON BRAVES ARE TO MOVE TO ALLSTON.: New Park to Be on Commonwealth.” Murnane, T.H. Boston Daily Globe. Dec 5, 1914. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Boston Globe (1872-1982). Pg. 1. ?

- http://sabr.org/research/braves-field-imperfect-history-perfect-ballpark#footnote21_81ugu0h ?

- “NEW PART TO SEAT 45,000.: Braves Will Have the Biggest Yet Built.” Boston Daily Globe. Mar 17, 1915. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Boston Globe (1872-1982). Pg. 7. ?

- Sporting Life (January 15, 1916): 8. ?

- In fact, the longest baseball game ever–26 innings–was played at Braves Field. ?

- New York Times, August 1. ?

- http://sabr.org/research/braves-field-imperfect-history-perfect-ballpark#footnote48_8co8ynz ?

- “Braves Field Bought by Boston University.” Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960). Jul 31, 1953. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Boston Globe (1872-1982). Pg. 1. ?

- “Toll Road to End at Route 128: New Plan Designates Weston-Newton Line” Daily Boston Globe. Aug 4, 1953. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Boston Globe (1872-1982). Pg. 1. ?

Alan – Many thanks from a retired member of the adjunct faculty of BU School of Law (Morin Center) for your remembrance of the Wigwam! In my retirement years, I’ve assumed the presidency of the Boston Braves Historical Association, a group dedicated to preserving the memories of the Boston Braves and Braves Field. From time to time, we’ve had our resident ballpark expert conduct tours of the field. He can identify where home plate used to be, the mound where Spahn and Sain pitched the Braves to the ’48 World Series, where the old Jury Box once stood, etc. Most recently, the tour was provided for a summer baseball symposium being conducted by BU professor Tom Whalen. Let’s hope that the university continues to preserve the administration building and portion of Braves Field’s right field pavilion for future baseball enthusiasts, BU faculty, students and parents to visit. In addition to our website posted above, we maintain a Facebook page: ttps://www.facebook.com/pages/Boston-Braves-Historical-Association/112965668820641. I’ll be linking your article from those sites and will be mentioning it to our membership in our eNewsletter as well as our quarterly hard copy edition. Hope it receives the attention from our group that it deserves. Thanks again!