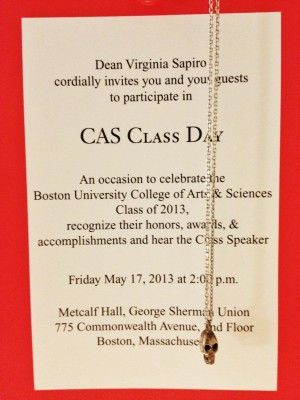

There are five full days of class left, and to my fellow seniors (as well as to myself) I ask:

Was it all worth it?

It’s a vague question that provides countless permutations–was going to college, and majoring in the humanities, worth my time and my sanity? It’s a question that is also centered ominously on economics: was entering college, and majoring in the humanities, worth the money spent and/or loans taken?

Standing before this major threshold, I think the question is worth debating when figuring out what job will suffice to pay back loans at minimal installments, but still will engage with past studies. (What do you do with BA in English?) I’m sure many college seniors currently face this dilemma, regardless of their discipline. Our shared concern seems to be indicative of a clear epistemological shift in how our society views higher education.

Frank Bruni recently highlighted this changing mission of college at the state level in the New York Times:

“…Colleges in Virginia are now required to provide information for a database that shows what graduates majored in and what they wound up earning 18 months after getting their diplomas. Florida lawmakers have toyed with encouraging students to study engineering by making their tuition cheaper than humanities majors’. Pat McCrory, the new governor of North Carolina, recently advocated legislation to distribute funds to the state’s colleges based not on their enrollments — or, as he said on a radio show, on ‘butts in seats’ — but instead on ‘how many of those butts can get jobs.’”

He goes on to quote the North Carolina governor as saying, “If you want to take gender studies, that’s fine, go to a private school…But I don’t want to subsidize that if that’s not going to get someone a job.” Today’s reality seems to dictate that a BA diploma should immediately mean a career, which is a fine equation given our hyper-consciousness of economy. However, this emphasis on landing that high paying job seems to exaggerate the importance of the school bequeathing that diploma in May. And so, I’m prompted to consider when education became a commodified object, and how this commodification affects learning at the grade school level and beyond.

My college application saga is nothing but average: it was spring of 2009, and I was choosing between BU, a private college in Pennsylvania, and an equally prestigious state school. I was rejected from every “dream” school, those schools one applies to only to say they did, those same schools I thought I really wanted to go to solely based on their inherent prestige (including one not too far down the road from the Charles River campus).

The first rejection hurt the most. After years of being told how you are so wonderfully bright by family members, and how you are a pleasure to have in class by teachers, being told “No, sorry” by top-tier universities feels like an insufferable blow.

Which is why, to a certain extent, I understand where Suzy Lee Weiss, a high school senior whose op-ed on college rejection was recently published in the Wall Street Journal, is coming from. Being told you will not be where you thought you should be after working so tirelessly in high school, to be blunt, sucks, especially when high school so eagerly fuels this push for college acceptances.

In an interview, Weiss shared how she had cried to her mother after receiving rejections on April 1st from the Ivy institutes she wanted to attend. I think back to where I was, and how I felt, the first of April, 2009, 5pm. I refreshed pages, knowing I’d be reading a lot (two that day, if I recall correctly) of “I regret to inform you”s. When I finally got the expected responses, I don’t even think I shed a single tear. All I remember from that night was sitting on the floor of my recently painted bedroom, talking to friends on iChat (remember when that was a thing?), actively distracting myself from an AP English Literature paper I didn’t want to write.

I chalk up my lack of tears, of sadness, to not really knowing what I wanted. I was a well rounded, above average (whatever that means) student, who would probably get accepted to some school, somewhere. Did it really matter what name brand school I, or anyone else, chose to attend? I’d say the answer is no. This notion of finding pride in a school name alone is what I really consider problematic, not only within Weiss’s letter, but also within our contemporary society, because it induces an unnecessary anxiety about Where I Go to College, and attaches an reprehensible sense of entitlement to outstanding achievement in high school.

“Like me, millions of high-school seniors with sour grapes are asking themselves this week how they failed to get into the colleges of their dreams. It’s simple: For years, they—we—were lied to.”

Weiss isn’t far from the truth–students everywhere I think are lied to throughout grade school. However, students (myself included) instead are constantly fed the fiction that attending a well-known school is the status symbol of success post-grad; if I can’t put a reputable school’s bumper sticker on my Toyota, I probably shouldn’t bother driving to school.

At my middle school they always did “College Awareness Day” for sixth graders, providing each doddering pre-teen with an over-sized college t-shirt from a nationally famous institution. I received that day a marigold UC Berkeley shirt, size XL. It meant nothing to me, but the world to my mother: “That’s a great school. I’d love it you went there one day.” (I missed applying to the UC system by one week. A dream dissolved, and a t-shirt shoved into a closet. My mother never even wanted me to travel that far away from home anyway.)

After that day, I was aware of two things: (1) that I must go to college and (2) that college apparel, more importantly, makes you look cool and intelligent. I remember zero specifics about the importance of a college education, clearly too preoccupied over getting free “stuff” from school. In retrospect, this t-shirt seemed to say, “Land here, and all your problems, your concerns will disappear,” and, most importantly, “Here, have all these job offers because you are beautiful and deserving in your UC gold and blue.” (Your BU scarlet and white, your Harvard crimson, etc.)

This fiction is still looms at the university level, at least to some extent. I was visiting Chicago a couple weeks ago, and had the opportunity to overhear some undergrads chatting about an extracurricular event which could only have insulted those (them) from the top-tier institutions in the greater Chicago area. Those from public schools, however, they really needed that lesson about the dangers of acting inappropriately on social media because stupidity clearly occludes those deemed more intelligent by the institutions they call home. Their hard-earned labels as students of their elite university seemed to be the only thing noteworthy, based on their prejudice alone.

Again, I quote Frank Bruni: “Do we want our marquee state universities to behave more like job-training centers, judged by the number of students they speed toward degrees, the percentage of those students who quickly land good-paying jobs and the thrift with which all of this is accomplished? In the service of that, are we willing to jeopardize some of the trailblazing research these schools have routinely done and the standards they’ve maintained?” In other words, are we willing to forgo the positives of a well-rounded education for a degree that merely says “I’m hire-able”? Should education only be seen as a means to an end?

Looking at Weiss and other downtrodden, rejected high school seniors, who all are grieving the loss of their dreams, crying bitterly to the world, seem to rival a child crying over a toy their parent refuses to purchase. Is this a harsh comparison? Probably. I do think it’s slightly unfair that the free t-shirt handed out in middle school is swiftly taken back with each rejection, left dangling out of reach, as reality quickly descends upon the fantasy of attending Your Dream University™, bearing ominously dark shadows of incumbent unemployment. Nevertheless, I still get the sense that these dream schools are only dream schools in the same way that a fashion forward individual desires that designer pair of shoes. We want to drip with prestige of an Ivy alumna because we are consistently shown that this path is a surefire way to success, and to own those designer pumps at the same time. (I mean, have you seen the Harvard Club on Commonwealth? I rest my case.)

I myself am obviously guilty of buying into this purported fiction to a certain extent. I mean, I did choose BU–a brand name in its own right, but I’ve also recently accepted an offer from a graduate school program which more or less sold itself on its providential job offerings inside and out of academia. I was nonetheless skeptical of this propaganda. And so I visited, but then was still skeptical, if not more so. Only when a current professor of mine told me that I should go only if I truly believe that the program will make me a better person, did I find confidence in my decision. Sure, the name of my new school may be important, but what is more considerable, more momentous is what I will gain as an academic, and as an individual.

This same piece of advice I have received so near the end of my undergraduate career is one I’d wish I’d heard more in high school. It’s also one that I think would spare a lot of parents and students grief over college rejections. If we stop jumping the gun, and seeing that stain of unemployment at the moment of these same rejections from dream universities no matter what tier, and instead think about how college education will shape the minds our next work force, maybe this insane view of valuing education as we would a designer bag or expensive car will finally be put to rest.

And so, to answer the question of whether or not these past four years were worth it all (whatever “it” is), I’d say emphatically that yes, it was. I am who am I today because I chose to study the humanities, because I chose to attend BU, because I chose to live in Boston. And that, no matter how idealizing or sentimental it sounds, will never have a definitive price tag.

One Comment on “The Senior Struggle: Was It All Worth It?”