Glory is the story of an entirely black unit of the Union army during the Civil War, told from the point of view of its white commanding officer. Mississippi Burning centers on two white investigators looking into the murders of three civil rights workers, one black. To Kill A Mockingbird, as you well know, sees the upstanding, white Atticus Finch defending an innocent black man. Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained follows a freed slave’s quest for revenge, helped along by a white bounty hunter.

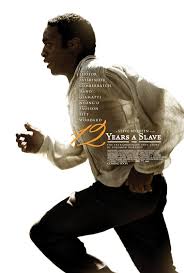

Hollywood has an ugly habit of telling minority stories through the eyes of white men, softening what could be powerful political messages to assuage white guilt. That’s why it’s refreshing and shocking at once to see Steve McQueen’s brutal 12 Years A Slave, a story about slavery told by those who suffered through it, that doesn’t attempt to soften the harsh realities of the past.

Solomon Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor) lives happily as a free man with his family in Saratoga, New York when he is approached by two men in a bar offering him a lucrative traveling gig as a violinist in the circus. After a few too many drinks in celebration, Solomon passes out. He wakes up the next day to find himself chained and shackled, and soon after, beaten. His proclamations of freedom fall on deaf ears and Solomon is sold into slavery, first to a New Orleans plantation owner named Ford (Benedict Cumberbatch). After a scuffle with an overseer and a near-hanging in retaliation, Solomon is sold again, this time to the crazed, alcoholic Epps, played with animalistic ferocity by Michael Fassbender. In the remainder of Solomon’s 12 years in captivity, McQueen showcases the everyday realities of slavery—the beatings, the rape, the humiliation, the savagery—and holds nothing back. The story is all the more resonant because it’s true. The real Solomon Northup published an autobiography of the same name in 1853.

As in his previous films Hunger and Shame, McQueen turns the human body into a grotesque canvas for brutality. Slaves in this movie are frequently stripped naked, washing themselves from buckets in a farm yard or put on display for prospective buyers like prized livestock. Victims of beatings bear painfully realistic scars to accompany the deadened look in their eyes. They are less human beings than wraiths, floating through their cabins and cotton fields, resigned to their fates.

The violence in 12 Years A Slave is unsettling to say the least, not in a Saw-like way, but in a realistic, horribly inhumane way. There is no cartoonish antebellum charm or happy-go-lucky field hands, simply real people performing real atrocities on each other. In the film’s most haunting scene, Solomon is left hanging from a noose, toes barely scraping the ground as he struggles to remain upright while skating through the mud. Behind him, other slaves go on about their day with hardly a look in his direction. Day turns to night. One brave soul gives him a few sips of water. All the while, Solomon is gagging, grasping for life until he is mercifully cut down. Frequently in 12 Years A Slave, background characters seemingly take no notice of events like these—hangings, beatings, rape. The genius of the film is its ability to convey such incidents as everyday occurrences. Its power is reminding viewers of the countless unnamed slaves who never knew freedom, whose lives were this and this only. By framing the narrative through the eyes of a former free man, McQueen manages to depict the era’s atrocities from the inside while making the witnessing of them relatable.

Yet the film’s sense of morality is more sophisticated than the oppressed blacks pitted against the evil whites. 12 Years A Slave raises other questions—is the free man who leaves his fellow slaves behind wrong? Is it okay to savagely beat someone under threat of your own life? Is the kind white man who owns slaves still a bad person? Grantland’s Wesley Morris suggests that these questions can be traced to the present day, as “the seeds of black anger, black self-doubt, black resilience, white supremacy, and white guilt.” In that context, 12 Years A Slave becomes equally critical of the present day, the rare film that transcends simple narrative and becomes cultural commentary (and an intelligent one, at that). In an interview, McQueen spoke about his desire for his movie to spark conversation about “where we are right now within the context of slavery. Look at the prison population. Look at the mental health issues, the poverty, the unemployment.” It’s a sobering but oft-overlooked notion that the seeds of today can be traced to the mistakes of our ancestors over 150 years ago.

12 Years A Slave is an interesting companion to Fruitvale Station, another 2013 release that brought race relations to the forefront of Hollywood in an unflinching, honest way. Is there a through line in history that somehow ties the fates of Oscar Grant and Solomon Northup?

Don’t just see 12 Years A Slave, but think about it. Think about what it takes for a society to condone what you’re seeing on screen. Think about a cultural identity being inextricably tied to events of the distant past. Think about its repercussions in the world you live in today. Think about it.