There are definitely certain situations in which it is appropriate to read “The Catcher in the Rye.” Generally these fall into the following categories: if you are between the ages of 13 and 18 and (1) have been assigned it in school, (2) have been discouraged from reading it by a parent, teacher, or school board, (3) just found out that it used to be banned in schools, or (4) are a baby-boomer just pretending to be a teenager again. Oh, and not to mention if you feel pressured to pick it up because everyone else has read and loves it.

There are definitely certain situations in which it is appropriate to read “The Catcher in the Rye.” Generally these fall into the following categories: if you are between the ages of 13 and 18 and (1) have been assigned it in school, (2) have been discouraged from reading it by a parent, teacher, or school board, (3) just found out that it used to be banned in schools, or (4) are a baby-boomer just pretending to be a teenager again. Oh, and not to mention if you feel pressured to pick it up because everyone else has read and loves it.

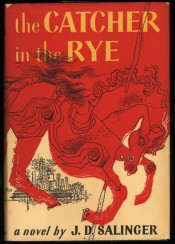

That last reason is why I picked up the (mis)adventures of a good ol’ Holden Caulfield. Unfortunately, I read the book both too early in life (sometime in middle school) and too late (before sophomore year of college). So instead of ever seeing Holden as a reflection of my teenage angst and dissatisfaction with the world or having the “Salinger gets me!” notion, I just hated Holden. To this day, I can’t think of a character from any book that I dislike more, even considering those that some would consider vile. At least villains like Heathcliff have some passion about them; I’ve always considered Holden to be apathetic, or at best, inactive in response to his discontent. My dislike of Holden gave rise to a host of other personal issues with the book, including giving it a B- in terms of “stream of consciousness” quality and utter disgust at Holden’s lack of maturation as the book wraps up. All the wanton cursing I can get into; I just wish a similarly likable plot accompanied it.

However, when J.D. Salinger died this past January and my disgust with the popularity of his most well-known novel was rekindled, I decided to/was encouraged to dive a little deeper. I started with “Nine Stories,” then moved onto “Franny and Zooey,” and finished with “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction,” and eventually realized that I love Salinger. It blows my mind that “Catcher in the Rye” is considered Salinger’s chef-d’oeuvre. Creating Holden Caulfield and capturing the essence of the teenage years is not nearly as remarkable as the characters, plot, and dialogue of his other works.

However, when J.D. Salinger died this past January and my disgust with the popularity of his most well-known novel was rekindled, I decided to/was encouraged to dive a little deeper. I started with “Nine Stories,” then moved onto “Franny and Zooey,” and finished with “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction,” and eventually realized that I love Salinger. It blows my mind that “Catcher in the Rye” is considered Salinger’s chef-d’oeuvre. Creating Holden Caulfield and capturing the essence of the teenage years is not nearly as remarkable as the characters, plot, and dialogue of his other works.

If after reading this, you decide to shoulder the task of reading the rest of Salinger’s work, I would suggest that you read the aforementioned pieces in the same order that I read them. I was encouraged to follow this order by a friend, and she knew what she was talking about. “Nine Stories” is a fairly easy read, but also gradually introduces you to the variety of characters and themes that Salinger explores. (I’m still getting over the breadth of view of humanity and thought related in these short stories.) Just as importantly, you get used to his use of dialogue and monologue, which, yes, is apparent in “Catcher in the Rye,” but is not at its best, at least in my opinion. That’s found in “Franny and Zooey,” a book dominated by the conversation between two (extremely well-read) siblings in the Glass family, one of whom is undergoing a life crisis. “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction” is really two stories, both told by Franny and Zooey’s older brother: the first, recounting events after an almost-wedding, the second, well, introducing Seymour Glass.

If after reading this, you decide to shoulder the task of reading the rest of Salinger’s work, I would suggest that you read the aforementioned pieces in the same order that I read them. I was encouraged to follow this order by a friend, and she knew what she was talking about. “Nine Stories” is a fairly easy read, but also gradually introduces you to the variety of characters and themes that Salinger explores. (I’m still getting over the breadth of view of humanity and thought related in these short stories.) Just as importantly, you get used to his use of dialogue and monologue, which, yes, is apparent in “Catcher in the Rye,” but is not at its best, at least in my opinion. That’s found in “Franny and Zooey,” a book dominated by the conversation between two (extremely well-read) siblings in the Glass family, one of whom is undergoing a life crisis. “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction” is really two stories, both told by Franny and Zooey’s older brother: the first, recounting events after an almost-wedding, the second, well, introducing Seymour Glass.

While reading “Franny and Zooey,” I realized that the Glass family, not Holden, is Salinger’s masterpiece. Because they are involved in nearly all of the short stories in “Nine Stories” and both novels (ignoring “Catcher in the Rye”, it would be impossible to truly convey the nature and significance of Glass family in brief. Know this: Bessie Glass’s children are, quite simply, geniuses. The knowledge and thought process required of Salinger to create stories around, dialogue between, and monologue from these children is not apparent in “Catcher in the Rye.” To expound upon teenage angst is unexceptionable, no matter how well it’s done. To remark on the general human condition through a variety of extraordinary yet flawed, and as a friend said, “brilliant and tragic,” characters is incredible. As in the bulk of literature, the character that is perfectly relatable is not as interesting as the one(s) who challenge us.

Special thanks to friend and fellow Quad writer Anna Ward for making this article possible.

I wholeheartedly agree with you about Catcher in the Rye. I read it during my junior year of high school. We read it mostly for its “look this is not just a hat, it’s a symbol” qualities. Either way, I hated the book. I am glad to hear that there might be some redeeming qualities to Salinger’s other works.

Is our falling in love with members of the Glass family on par with the “Salinger GETS me” notion? Nonetheless, an unpretentious bouquet of very early-blooming parentheses for this article. ((()))

Yea, I definitely hated Holden when I read it in high school. I just hope I wasn’t that apathetic/annoying as a teenager..You do make me want to check out his other books though.