The United States is a nation that prides itself in the fact that it was born out of the collective dissatisfaction of its citizens. The right of the people to peaceably assemble is explicitly protected in the First Amendment, and is considered by many to be one of the most important rights Americans claim. In the last year, protests from the discontented left – starting with the outrage that followed Scott Walker’s attack on Wisconsin unions last winter – have grown in size and scope, culminating in the Occupy protests, the most significant social movement in a generation. Unfortunately for the protesters, getting the country’s attention is not enough to generate meaningful change.

Ever since the Occupy movement began, voices in the media have been making comparisons to the widespread protests of 1968 in the United States and around the world. Occupy protesters themselves have made comparisons to the May 1968 student movement in France, which occupied university and government buildings in Paris. However, the comparison is not necessarily a favorable one.

In 1968, the United States was facing fatigue from years of war, a struggling economy, a young generation of leftists discontent with their government, and was in the midst of a Presidential election. These conditions, similar to the ones the country faces today, created a huge social movement characterized mainly by directionless anger and populated mainly by young people. The protests of 1968, despite their valid goals, led to a chaotic presidential primary, riots at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, bouts of police violence, and the eventual election of Richard Nixon by a frightened and reactionary voting population. The movement succeeded in gaining national attention and momentum, but in the end the main outcome of that leftist, populist movement was a serious swing in the pendulum back towards Conservatism.

The 1968 French student protests lasted only two weeks, but almost succeeded in bringing down General Charles de Gaulle’s government. The students occupied buildings at the Sorbonne, marched in the streets of Paris, and forced the French government to take notice of their demands for workers rights and a more decentralized government. There were significant conflicts between the police and protesters. The movement is still lauded today as one of the great achievements of protests in France. But after the two weeks of marches and occupations, very little changed about the way the French state operated, and de Gaulle and his government were easily re-elected.

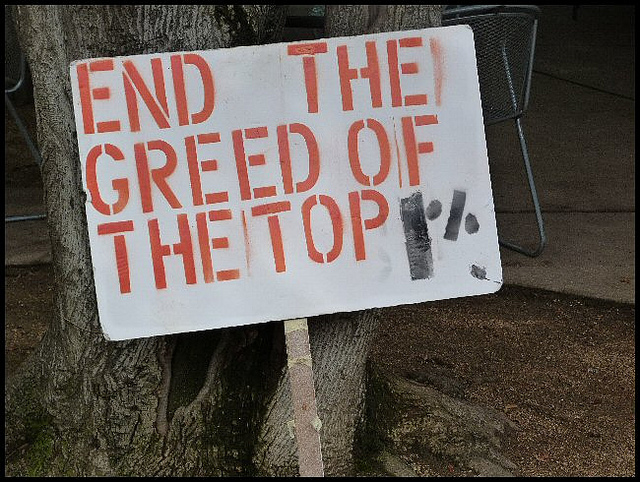

Both of these movements bear resemblances to the current Occupy movement in the United States. They were born out of general frustration, a weak economy, and a feeling that the cards were stacked against the young and the underprivileged–that the possibility of advancing a few rungs on the social ladder was no longer real. The protests of 1968 lacked clear, direct demands. The Occupy protests have reveled in their refusal to come up with concise lists of changes that should be made, holding instead to the opinion that cutting all of their grievances down to a list of specific demands would decrease the populist appeal of the movement.

Occupy just saw its most violent week, with police throwing cans of tear gas into crowds in Oakland and arresting dozens. A young Iraq War veteran was critically injured after reportedly being hit in the head by a “police projectile.” The opening of hostilities between protesters and police represents a rupture with the model of protests like the one in Wisconsin last winter, where police refused to evict protesters from the State Capitol.

If the Occupy protesters want to do anything other than simply change the conversation – a goal they have already achieved – they need to change their methods. Generalized frustration and anger lead to ineffective protests and tend to leave the general public more sympathetic towards government than activists. The United States finds itself at a political crossroads, facing economic problems and widespread public discontent, the usual precursors of governmental upheaval. The way the pendulum swings will depend at least in part on whether the Occupy protesters are able to focus their frustration, and put a serious face on protests that some see as youthful rebellions. If the Occupiers find a way to work with the system they abhor in order to change it, the left may get a second chance in 2012. If they continue to cleave to their principled distrust of all things establishment, Herman Cain may just be the next president of the United States.