By Becca Tarvin and Caitlin Clancy

Despite mankind’s significant achievements in the field, there is little recognition for the fascinating discoveries made in animal reproduction. Humans are not the only creatures that engage in creative and bizarre sexual acts. In fact, even animal species considered “common” partake in some extraordinary sexual behavior, or are endowed with some surprising equipment. Here we will explore some of these unusual cases of reproduction from a few unassuming species, in hopes to illuminate the incredible complexity of which all animals, vertebrates and invertebrates alike, are capable of.

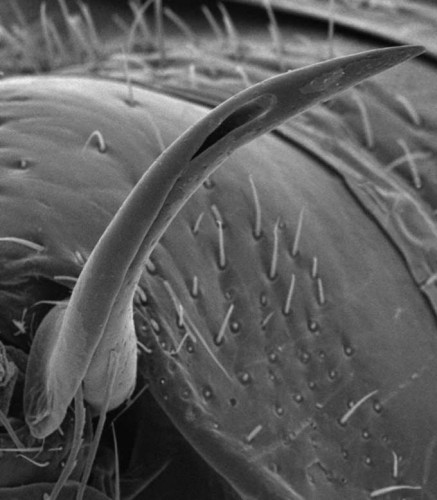

Although we’re certain you have heard of bed bugs (Cimex lectularius), we can almost bet that you’ve never heard about their approach to reproduction, known as “traumatic insemination.” Without any sort of courtship, a male bed bug will mount a slow-moving, blood-engorged female and probe her abdomen with his aedeagus (a bed bug’s penis) in search of the penetration site. Using his “needle-like” organ, the male then punctures the female’s abdomen to inject sperm. The female is subjected to an average of five successive mating rituals every time she feeds, usually with different males. Each copulatory act negatively affects the female’s health, even though the penetration area, or spermalege1,2, has special immune responsiveness. Also, males are capable of detecting non-virgins, and deliver 75% less sperm to these females since they are more likely to be already fertilized3. Life seems good for male bed bugs, but in some species they too are “traumatically inseminated” if they are mistaken for the wrong sex. In these instances, males often die because they lack the protective equipment that females possess.

Perhaps you’ve encountered this scenerio: You’re sitting idly near a pond, and you notice two waterfowl, male and female, in what appears to be a fairly harmonious pairing. What you do not realize is the struggle that took place for that male drake to acquire that female duck. The female’s oviduct has evolved to be incredibly complex, and functions as a sophisticated anti-rape mechanism. Her anatomy may include spirals and nooks, making entrance virtually impossible without her consent. Male drakes have coevolved to counter this morphology by having intricate, sometimes full-body length, corkscrew-like phalli4 that wind oppositely into the female’s anatomy. However, females also have the ability to stow away unwanted sperm from aggressive males and eject it later, so only the longest and most desirable males are permitted to fertilize them.

Another interesting case is snails, which are a bit more exciting than you’d guess. As hermaphrodites, they possess both male and female reproductive organs, yet they cannot self-fertilize. These organs are actually located by their eye stalks, which ogle each other during the 4-6 hour mating marathon. Males have an option to enhance sperm passage in the form of “love darts”– calcium-rich and mucus-covered spears that are shot at and received by the female. If the love dart hits its target (most miss completely), the mucous causes the female organ to contract, allowing more sperm to enter during actual intercourse5. The sperm packet is then moved to a storage area inside of the female, where it may wait up to several months before being used for fertilization. The female can selectively digest or use the sperm she catches in order to permit fertilization by the optimal male. Of course, this system has its cost: females often avoid the love darts because they pierce their bodies in a way similar to traumatic insemination. This tactic improves the reproductive success of the initial male shooter and gives his sperm a chance to compete6.

Consider also the banana slug (Ariolimax Dolichophallus), another hermaphrodite that participates in an unusual fertilization ceremony. First, two individuals fully extend their phalli to size up each other. This is a crucial step, because these slugs have enormous penises that can reach their full body length– that is, 6-8 inches or more, which is impressive even by our standards. In fact, their Latin name Dolichophallus translates to “giant penis”. The male parts must be roughly equivalent in size, or else the larger male will become stuck during mating. If the sizing is miscalculated, the solution is pretty morbid: the other slug will literally chew off the superfluous penis to separate the two and thereby truncate the larger male’s original size7. During reproduction, the two lay out a thick slime bed to ease the transaction, and even sample each other’s slime in order to gain some hormonal information and/or nutrients from one another.

Of course, all of these specialized features and the associated behaviors aren’t just occurring for the sake of sexual daring. Females typically invest more in the reproductive cycle, from the egg itself to gestation and eventual parental care. Consequently, females are highly selective when choosing a mate, and are interested in whoever exhibits the best fitness and thus the best genes to pass along to their offspring. These high standards often result in sexual resistance, which males accommodate in a number of ways– in these examples, their method is often forceful and strange. Ultimately, the female is still typically able to pick which donor will fertilize her. Considering that this is only a fraction of the instances of peculiar animal sex, maybe we can better appreciate how Mother Nature has granted deviation and ingenuity in the sack beyond our own species.

1. Stutt AD, Siva-Jothy MT. 2001. “Traumatic insemination and sexual conflict in the bed bug Cimex lectularius. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98(10): 5683–87.

2. Reinhardt, K.; Naylor R.; Siva-Jothy, M. T. 2003. Reducing a cost of traumatic insemination: female bedbugs evolve a unique organ. Proc Biol Sci. 270(1531): 2371–2375

3. Siva-Jothy, MT. 2006. Trauma, disease and collateral damage: conflict in cimicids. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of Biological Sciences. 361: 269-275.

4. Brennan, P.L.; Prum, R.O.; McCracken, K.G.; Sorenson, M.D.; Wilson, R.E.; Birkhead, T.R. 2007. Coevolution of male and female genital morphology in waterfoul. PLoS ONE. 2(5): e418.

5. Koene, JM; Chase R. 1998. Changes in the reproductive system of the snail Helix aspersa caused by mucus from the love dart. Journal of Experimental Biology. 201(15): 2313-2319

6. Chase, R; Blanchard, KC. 2006. The snail’s love-dart delivers mucus to increase paternity. Proc. R. Soc. B. 273:1471-1475.

7. Leonard, JL; Pearse, JS; Harper, AB. 2002. Comparative reproductive biology of Ariolimax californicus and A. dolichophallus (Gastropoda: Stylommatophora). Invertebrate reproduction & development. 41: 83-93.

Bed bugs are highly evolved for being so repulsive in their mating habits. They can reproduce exponentially in a short amount of time. Most people find out they have bed bugs a couple of months after they have established themselves in their home. Contact a professional if you think you have bed bugs. If you are traveling and staying at hotels or motels, you can watch a detailed video showing how to inspect a hotel room for bed bugs so you can sleep easy. http://www.bedbugsnorthwest.com.