I recently had the occasion to buy children books. Not creepily, as one might gift lollipops on playgrounds, but rather, to kids with whom I am (well-) acquainted. The first is my now two-year old niece, who I’ve almost bought a dozen books, and yet hasn’t gotten any. It’s hard for me to commit to a picture book, especially when I can instead opt for a baby-sized Ray Lewis jersey.

I recently had the occasion to buy children books. Not creepily, as one might gift lollipops on playgrounds, but rather, to kids with whom I am (well-) acquainted. The first is my now two-year old niece, who I’ve almost bought a dozen books, and yet hasn’t gotten any. It’s hard for me to commit to a picture book, especially when I can instead opt for a baby-sized Ray Lewis jersey.

But I did, with great success, purchase a book for my ladyfriend’s little Communist (i.e. adopted Russian) brother. Without really thinking about it, I bought him my favorite book from my younger years, Jerry Spinelli’s “Maniac Magee.” While waiting for the opportunity to give it to him, I of course began to leaf through the pages.

What struck me as I reread a book that I’d read over a dozen times was probably the same thing that struck my mother when she first looked at the book that her son was newly obsessed with. “Maniac Magee,” though incredibly accessible and captivating to young readers, refreshingly, albeit somewhat subtly, addresses issues that some may not deem “age-appropriate.” Spinelli’s work weaves concepts of racism, alternative family structures, and myth-making into a deceptively simple story of a kid who runs everywhere.

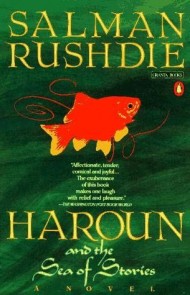

It was but a few days later that I read (for the first time) Salman Rushdie’s “Haroun and the Sea of Stories.” I didn’t realize that the target audience was children when I began the book; I only had a vague notion of that fact when I finished. Only after a little research did I realize that Rushdie wrote the book in response to his son’s request that he write books children could read. But again, what may read to a child as a fantastic fairy tale should read to one with a more mature and keen eye as an allegory, one that, among its chief priorities is the process behind the formation of stories themselves. Like, whaaat?!

And so, I come to this conclusion: (some of) the best books are those that we can enjoy as children and continue to enjoy and learn from as we mature, encouraging us to pass them down to the children we know. They induce a cycle of loving literature.