It doesn’t take long for Inside Job to make the blood begin to boil. The film opens with sweeping shots of the majestic Icelandic countryside. Soon, purple mountain magnificence and lush olive valleys give way to dynamite ripping apart the landscape as greedy banks strip the land of value. A quick cut away and we’re in a New York City set to Peter Gabriel’s’ “Big Time”, that wretched hive of suits and ties where corporate skyscrapers dominate the skyline and a fleet of airplanes wait for their masters’ beck and call. It’s extravagance without limit, and one can’t help but feel a tinge of envy for these super-elites. That envy will soon lead to fury.

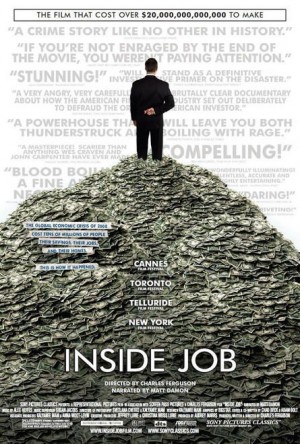

Inside Job, a documentary by Charles Ferguson, recounts the global economic collapse of 2008, giving detailed background into the deregulators who set the system up to fail, and the greedy investment banks who cast their fellow citizens aside for fabulous riches. The film is a damning indictment of these men, from the CEOs of Merrill Lynch and JPMorgan to Alan Greenspan and the FED, and few escape Ferguson’s piercing eye.

Ferguson tackles the winding backwoods of financial intrigue with grace. It’s an exclusive country club, one so confusing that many insiders explain their tenure by merely being able to understand how the system works. But Ferguson proves them wrong, explaining complex terms with ease using monochromatic animated charts and data set against a black background. His uncanny ability to boil down the entangled web of the financial system is the touch of a real talent.

Ferguson’s film lacks the bombastic confrontationist tendencies of a Michael Moore, who recently put his rage into a different documentary about the financial meltdown called Capitalism: a Love Story. But Capitalism became too enveloped in outrage. By the end of the film, the emotional drama is overpowered by Moore’s own fearless (and foolish) theatrics. Ferguson by contrast is simpler, calmer, and treats his audience with bit more respect. Ferguson is not preaching to the choir; he rarely preaches at all. Instead, he channels our collective considerable frustration, probing where newsmen and politicians dare not go.

He greets his interviewees not with righteous fury, but with disbelief. He never raises his voice, never drowns out the answer, but will interrupt with a damaging fact. Ferguson is all too happy to skewer the traders with title cards stating they “declined to be interviewed on film,” or hold that silence a few seconds too long to watch them squirm. He’ll even go so far as to interview a brothel owner, highlighting their excesses of pleasure as particularly sadistic.

But Ferguson also shows a deft hand in building emotion in the film. While the documentary easily sends chills of rage down the viewers’ spines, it also, all too briefly, grounds the film in real suffering, which only fuels our anger. While CEOs relax in luxurious penthouses or private jets, Ferguson sends us to Florida, where a tent city and its downtrodden residents inspire something more than just sorrow, but genuine sympathy. We see how a system these homeless Americans had no hand in building has destroyed their lives, and rewarded the very fiends who ruined them. Beyond America, Ferguson travel to Singapore and China, where an emotional factory worker speaks in broken English of the impending tsunami of financial ruin that is headed their way. Their plight is horrifying; unlike Americans who woke up to a crisis, these workers see their doom approaching and are helpless to stop it. While Ferguson allows international critics to jab the insiders, the international pain caused by the big banks’ failures is his strong suit and one I wish he played more often.

When interviewed, those villainous bankers, insiders and academics sit smugly across from Ferguson, smiling away questions and falling silent when caught in their deceits. We can feel the dishonestly oozing beneath their finely-polished skins, but it rarely jumps to the forefront.

Surprisingly, none of the baddies of the documentary storm out of the interview in protest, with one notable and shocking exception. Glenn Hubbard, a slim-builded economist and dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Business, gets caught up in Ferguson’s trap when the director asks Hubbard about contributions he received from government entities while writing a research study praising Iceland’s faulty economy. Hubbard initially dodges the question, telling Ferguson his time is almost up.

But Ferguson senses blood. He presses on, and for a shining moment, Hubbard lets his guard down. The veneer slips and before our eyes Glenn Hubbard transforms from mild-mannered intellectual to scheming monster. His eyes blaze like a cornered wolf, his mouth contorts into a vicious scowl and his brow furrows with heartless rage. “You have three more minutes,” he sneers. “Give it your best shot!”

It’s a moment of stark clarity the film had been building towards, and one of the highlights of what is a surprisingly emotional documentary. Inside Job has its faults, as the narration by Matt Damon is nothing short of textbook dry and what should be a triumphant call to action at the film’s close is sadly reduced to a cliché. But when the film hits its stride, it’s a sight to behold.

Despite a dry narration, Inside Job is an insightful, engaging, and enraging example of documentary filmmaking at its finest: A-