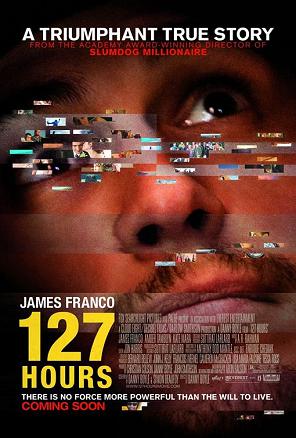

In the opening shot of Danny Boyle’s 1996 breakthrough, Trainspotting, Ewan McGregor charges down a Scottish street with a wry smile on his face, propelled by the pounding floor-tom pulse of Iggy Pop’s “Lust for Life.” It is a moment that captures the exuberance of youth, and all the wistful rebelliousness that comes with it. It also provides a perfect snapshot of the soul Aron Ralston, the young adventurer who is the focus of Boyle’s new film, 127 Hours.

Working from Ralston’s own memoir, Between a Rock and a Hard Place, 127 Hours recreates the true story of the more than five days Ralston spent trapped alone in a barren Utah canyon, his arm crushed and pinned against the canyon wall by a dislodged rock. He told no one where he was going, had a dwindling supply of food and water, and no way to contact the outside world. By all indications, he was a dead man; he was merely passing time with the formality of dying slowly.

But Ralston did not die. After days of surviving by whatever means he could, recording last goodbyes to his family members on his digital camera, and rifling through visions that were part memory and part delirium, Ralston summoned up a kind of strength that few of us could fathom, using a low-quality swiss army tool to amputate his trapped arm and secure his escape. Faced with the prospect of death, Ralston chose to live at any cost, and perhaps that’s what makes this film so suited for Danny Boyle.

Boyle, whose films are marked by a sort of unhinged, hyperactive energy, wouldn’t seem like the natural choice for a film about a lone man who cannot move. Boyle is all about movement. While most dramas build on potential energy, working their way up to a climax, Boyle thrives on kinetics. His films are a constant release of force, often times as exhausting as they are entertaining.

But here, given the task of filming what is essentially a one man show, his penchant for movement and energy takes him out of the natural world around Ralston and into the cerebral realm inside of him. Boyle is able to highlight Ralston’s struggle by adding images and impressions of his life before the accident, the people he has left behind and those that he has under appreciated. It seems all of them will never be seen again. Often times these moments track Ralston’s own shortcomings, driven on by the overconfidence that got him into this mess in the first place. Other times they are simple, tender flashbacks that are reminiscent of the imprint a head leaves on a pillow, a dwindling reminder of something that once was but now is no more. These are small, not always profound instances, and Boyle’s stylization of the scenes wisely keeps the film from becoming a standard “life flashing before my eyes” story. These, Boyle says, are the moments that make up life, and they are the reason to continue living it.

Pulling this all together is James Franco’s brilliant, complete portrayal of Ralston. In a film where the audience knows the ending, it is an unenviable task to have to keep them invested in the struggle leading to the end. Franco does this by completely immersing himself in who Ralston is, capturing not only the quieter moments of desperation but also his manic resilience against the circumstances. He realizes he’s down but refuses to admit that he’s out. At one point he interviews himself on his digital camera, asking and answering questions about his choice to go canyon climbing alone, while a phantom audience laughs at his replies. His performance is great because even though we know he’ll escape in the end, he makes us fret regardless because we truly care about him. We want him to get another chance at life.

All of this leads up to the film’s penultimate scene: the amputation. There have been multiple reports of audience members fainting and seeking medical attention due to the graphic nature of the violence, but what ends up being more grueling than the visuals of the scene is the sound design. We’ve seen violence of a much more brutal variety on screen before, but rarely have we ever heard it the way it sounds here. Things squish, snap and scratch in a way that cannot be anticipated. Yes, it is jarring and difficult to watch, but it is never perverse or profane. It is a necessity, and it becomes all the more intense because while we root for Ralston we sit wondering to ourselves if we could muster the courage to do the same thing. At what cost could we keep ourselves alive?

Franco’s performance, combined with Boyle’s hyper active editing and frequent use of split screens, make 127 Hours easily watchable, saving it from being the endurance film that it easily could’ve become. Boyle finds in Ralston (through Franco) a perfect, living example of the kind of morals that have played out in his previous films. He is a filmmaker constantly inviting his audiences to keep living, to find beauty even in the worst places and situations, whether that be zombie infested England, the slums of Mumbai, the isolation of deep space or smack houses in Scotland. With 127 Hours he has crafted a love letter to existence itself, to the breath in our lungs and the ground at our feet. It is a film that urges us to keep going, to not give up despite the odds against us. To choose life.

Intense, focused and inspirational, 127 Hours is easily one of the year’s finest offerings, even though some scenes may be too much for the squeamish: A-

127 Hours is now playing at the Coolidge Corner Cinema and Kendall Square Cinema.