This Monday, the Institute for Astrophysical Research welcomed Catherine Espaillat, a member of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. She presented a lecture in room 502 in the College of Arts and Sciences, open to students and researchers alike. Her talk delved into some of the facets of her research in the field of protoplanetary disks of gas and dust, which form during the collapse of a star’s natal, molecular cloud.

Espaillat is young, but carries a bagful of accreditations. She graduated from Columbia University in 2003 with a Bachelor of Arts in Astronomy. She then went on to the University of Michigan where she received her Master of Science in Astronomy in 2005 and her Ph.D. in Astronomy & Astrophysics in 2009. The Boston University professor who presented a short introductory speech rapped out an extended list of honors. Among them is the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation’s Mellon Mays University Fellow and the Honors Astronomy and Astrophysics Postdoctorial Fellowship from the National Science Foundation. She speaks clearly, quickly, with fierce conviction. Her introducer described her perfectly with the way he ended his introduction: she is a member of his “Badass List.”

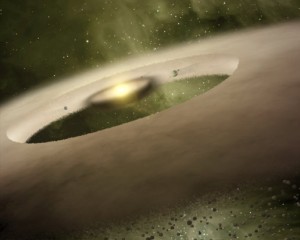

Her lecture revolved around the primordial protoplanetary disk of a star and its planets. These disks are composed of dust and gas, which evolve as time passes. The research she conducts focuses on what she referred to as “transitional disks” and “pre-transitional disks,” which are dust disks that have gaps and holes, possibly created by newborn planets accreting and stirring what is around them.

This lecture was definitely not your run-of-the-mill astronomy talk. As someone who hasn’t taken an astronomy class since the planetary unit of middle school science, I was completely overwhelmed by the detail, power, and enormity of her research. Her PowerPoint slides seemed to be in another language of large, complicated symbols and words; she drew conclusions from an array of diagrams and found meaning in small irregularities in intricate, multifarious graphs. Professors and researchers seemed to make up the majority of the attendees. They sat back, nodding along with her presentation, sometimes interrupting with a question. But as lost as I was, I felt the gravity of her research: she ended a section of her lecture by saying, “This will affect the way that researchers look at planet formation.”