Former Boston crime boss Whitey Bulger is the modern equivalent of the mythologized gangsters of yesteryear, and he is probably the most similar to the über-violent, remorseless mob characters seen in movies and TV shows. Historians will mention him in the same breath as John Dillinger, Pretty Boy Floyd, and Baby Face Nelson, as a criminal especially important in Boston for his dominance and his shaping of the South End. BU professor Dick Lehr, along with adjunct professor Gerard O’Neill, recently released Whitey: The Life of America’s Most Notorious Crime Boss, their third book about Bulger and his unique relationship with the FBI.

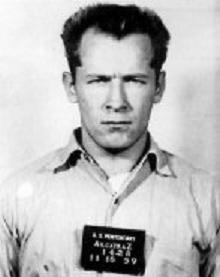

As a teen, Jimmy “Whitey” Bulger got involved with a local street gang and was cited numerous times for assaults and robberies. After stints in the Air Force, Atlanta Penitentiary, and Alcatraz, Bulger returned to South Boston and began to get involved with the Irish mob. Through assaults, robberies, murders, extortions, and other assorted mob activities, Bulger rose through the ranks until he gained a position of authority. As the head of the Boston organized crime scene, Bulger’s reign of power through the ’70s and ’80s was marked by extreme wealth and extreme violence. His arsenal of crimes soon expanded to include drug trafficking, arms dealing, and truck hijackings.

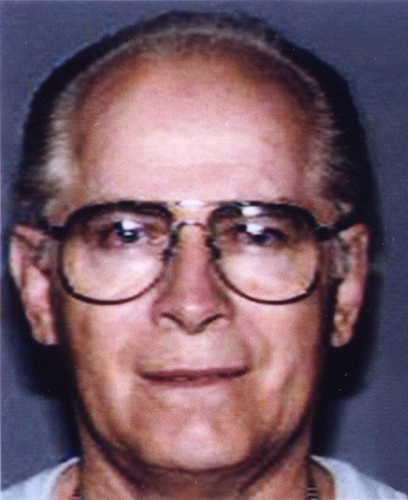

Bulger’s story is unique in that he was heavily aided and enabled by the FBI. While ostensibly an informant, Bulger developed a close relationship with agent John Connolly that allowed him to avoid consequences and further establish his power for years. The story of this relationship is chronicled in another of Professor Lehr’s books, Black Mass (soon to be a movie starring Johnny Depp as Bulger).

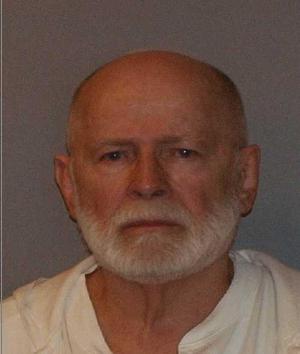

When a federal case was finally built against him in 1994, Bulger was forced to go on the run. His time on the lam was marked by travels across North America and Europe, with reported sightings everywhere from Oklahoma to London. His time as a fugitive became the stuff of lore and Bulger became a crafty, wily trickster figure continuously outsmarting the cops. His capture finally came in 2011 in Santa Monica, and he now awaits trial in Boston.

Professor Lehr sat down with The Quad to talk about his new book.

The Quad: I know you’ve written another book about Whitey Bulger. Can you explain how this one is different?

Professor Dick Lehr: Black Mass came out of reporting and work I’d done at the Boston Globe with a team of reporters, and that focused on what we now call the Black Mass years, a period where Whitey and the FBI were in this “Unholy Alliance.” It focuses on the corruption and the murders that happened, the drug dealing, the cover up, the protection, and the details of that. The thing about Whitey Bulger, in 1975 when he became a so-called informant for the FBI, he was already 48 years old, and he had already lived half a life. So the new book is where we take the Black Mass years and put them into the context of an entire life. It’s a biography that takes the Bulger family back to Ireland in the late 1800s to when they first immigrated to Newfoundland and Boston. What we need to do is what I think any biographer tries to do: not just tell the life story, but also try to figure it out. Get into the making of Whitey, the making of the monster.

Q: How did you go about gathering your research, determining what made it into the book, and with all that information shaping a narrative?

DL: Well, we got lucky in the sense that in terms of trying to figure out the first half of his life and what the factors were that influenced and shaped him, unsealed for the first time a few years ago was his vast prison records. He was in federal prison for around nine years and there were 500 pages of Whitey Bulger records that were not only about his prison life, like what he did, the trouble he got into, all kinds of things that were never known before that he did in prison, but also his early juvenile records, his school records, interviews with social workers, probation officers, and his family. You start to get a sense of the life in the family. So that became a huge, huge resource.

And then it’s just legwork. Whether it’s old court cases or talking to people, with his juvenile records, getting all his files from the Boston Police Department, getting his Air Force records… It’s almost like a stew: you put it all in the pot and then you have more than just the bare bones things. For 18 months, he was in Great Falls, Montana. He also got arrested there and went to jail for the first time in his life. So you get those records from the newspaper out there, and before you know it you have a chapter.

Q: Did you find anything from his early life that you think could explain how he would later act?

DL: Oh, yeah. Again, there are these contributing factors. You have to start with the fact that he is a psychopath. He’s different from you and me in the sense that he knows the difference between right and wrong, but doesn’t care; he has no conscience. Scientists can’t explain why we have psychopaths, whether it’s environmental, genetic or whatever. But then there are plenty of psychopaths that don’t become serial killers and crime bosses. And that’s when it gets into the family dynamics, his father, his life on the street, all of these reinforcing factors that propel him to where he’s successful and he’s somebody: he’s tough. The word we use is that he found a nourishment on the street that he didn’t find from his father.

The other thing is that he never had to pay. From an early age, he would get arrested and have to pay little consequence. So he had a sense of entitlement and became narcissistic, which is part of being a psychopath. He would be found guilty and it would get overturned; he would get sent to juvie and (the sentence) get suspended, and that went on throughout his whole life. He’s still avoiding consequences right now… And it just goes up the ladder of crime and he has this historic connection with the FBI that just propels him to the top of the underworld and keeps him there.

Q: In your research, did you find anything that was really surprising to you or that stood out?

DL: Yes, lots of different things. His participation in the LSD project in the late ’50s at the Atlanta Penitentiary was really fascinating. Just the detailed way which he served his nine years in prison was really fascinating. I think finding out about his father and why he hated his father, and how he realized who his father was in a way no one really has before, and the circumstances from which he came, which were incredibly intense and severe. When Whitey was seven or eight, his father was already in his late ’50s. He was a really old man, and the life expectancy for a man back there was like 60. So this was not a kid who was able to roll around and wrestle with his father on the floor or have any type of bonding. You start to get this sense of “Boy, it must have been strange.”

Q: I understand that there was at first a positive public perception of him. People thought he was a Robin Hood figure. How did he get that reputation?

DL: Two things: first, he fed it because he would do things like giving a family in need a turkey for Thanksgiving, like a politician would. You could trace that back when you find out about his teenage years. He was known to give a mother a ride home from the grocery store in his fancy convertible that he obviously stole or got from the proceeds of his crime. But he did nice things and he realized all through his life, even in Santa Monica when he was a fugitive, he was always nice to his immediate circle because it created a zone of loyalty and protection. There’s always something in it for him, it was always about him. You see this is a lifelong theme: that he wasn’t being philanthropic or generous. It was all about what would feel good for him or his immediate circle.

He’s also the kind of guy that showed people if you crossed him in any way, the same person that he gave a ride to yesterday he would kill tomorrow. Spreading that story, too, was his FBI agent handler, a guy named John Connolly, who was also from South Boston. He had a lot of relationships with reporters and Whitey was his secret informant, even if no one knew it at the time. But John Connolly was an FBI agent, and you have to understand the power of the media and the power of one agent that was corrupted and shaped the public perception. Connolly was very open and accessible to journalists covering crime in Boston. He would act as a background source or an informed source. I remember using him–a lot of people did–and it was great to have him and ask about investigations, or “Who’s this guy, who’s that guy?” No one ever knew that he was heavily involved with Whitey Bulger, but if you ever ask John Connolly about Whitey Bulger, he’ll say, “Oh yeah, he’s a real tough guy, he’s a killer,” stuff like that. “But he’s a good bad guy. He doesn’t let drugs into his neighborhood, they love him in Southie, he’s like a Robin Hood figure”–that was a line that came out of John Connolly.

Q: At what point did that change, or is it still there?

DL: Well, if it’s there, it’s somewhere in deep denial. It began with the Globe publishing a series–I was on that team in 1988–exposing Whitey, John Connolly, the FBI, and their special relationship. Through the ’90s and his court hearings, it all came out that he was an informant, a rat, and that he betrayed everybody. It was always about himself, and the kinds of killings he did–he’s truly a monster. Not anybody warm and fuzzy. There are people who still hold onto that idea, but they’re just in deep denial. All you have to do is open your eyes and look at the evidence.

Q: How did that relationship with the FBI come about?

DL: It was both institutional and personal. The FBI at the time, starting in the late ’60s and into the ’70s, had this program called the Top Echelon Informant Program. In their effort to go after the mafia, they set up this program where they were recruiting other underworld figures to get information on the mafia because that was their number one priority. So that was in play. In Boston, it was a very corrupt program–I can’t speak for other cities, but it was nothing like the corruption here. It was under the auspices of this program that the agent John Connolly reached out to Whitey. Connolly was about ten years younger than Whitey and had known him as a kid in Southie and admired him and the family, so he had a personal connection. It made Connolly’s career. He became a star in the office because–again this was all internal and hush-hush–but he landed Whitey Bulger and brought him into the program.

Q: What would have provoked Whitey to get involved in the program?

DL: He had a friend that had been protected. One of his associates had been an informant and it was clear that the benefits are that they will protect you, they will take out the mafia, and then the world is theirs. So he saw it in a very strategic way, as an amazing alliance because he was a lousy informant. He didn’t know much about the mafia. Connolly was more interested in being part of the Bulger mystique, plus it made him look good to the agency. The key thing was how corrupted it was. Strategically, Whitey could also see that he controlled Connolly right from the get-go. Connolly was almost at his beck and call, and Whitey sensed that. He was a very powerful, dominant personality, and instead of the agent controlling the informant, it was clear that the informant was controlling the agent. It was insane.

Q: To what extent did other authorities enable him or allow his criminal activities to go on?

DL: It was all FBI. There were divisions in the Boston Police Department that were trying to investigate Whitey Bulger, state police, the Federal Drug Enforcement Agency and the DEA–all through the ’80s were trying to go after Whitey, but Connolly had his feelers out. He would tell him, “Don’t go here, don’t go there, there’s a wire in your car, so and so is snitching on you.” Any effort that was made wound up being undermined and compromised for over a decade.

Q: So Whitey had to leave Boston, and he went on the run for 16 years. Why did he have to leave and how was he able to avoid authorities for so long?

DL: He had to leave because he had been indicted. His partners got arrested and John Connolly got word to him that they were looking for him. Finally, a band of prosecutors put together enough evidence to charge him, something that had never been done before. So he hit the road instead of going off to jail. For the first couple of years, he continued to stay in touch with his brothers and a key associate by the name of Kevin Weeks and got some inside information. I’ve learned from research that if you’re a fugitive of justice, the sooner you can cut ties to anyone you know, the better for you in terms of survival. By the end of 1996, he and his girlfriend were in California and had settled in Santa Monica and that was when they cut ties with Kevin Weeks. That was one huge way to explain how he survived in Santa Monica, because he was no longer in touch. Then Kevin Weeks folded, and there were all these things that could have led to his capture had they stayed in touch. Kevin led the authorities to where they buried a lot of dead bodies, but when he folded, his best guess was that Whitey was in Europe somewhere. We don’t know and no one will know if Whitey found a new way to stay in touch periodically with his brothers or his family here in Boston.

Q: Some people might have actually been kind of upset when he was captured, just because of the mythic proportions of what he’d done and how he was able to be on the run for so long. This happens a lot through history, with Bonnie and Clyde and John Dillinger especially. I was wondering why you think we mythologize these people when they’re killers.

DL: There’s the glamour of it, the indirect thrill of a violent, wild life. I don’t know. I can’t answer that, but if it’s distant and historical, I think it’s easier to try to glamourize and get into that side of it. I’m not aware of disappointment in Whitey’s capture; I’m just aware that it was a great day for justice since he had been wanted for so long, and I know the families and the victims’ families were happy that finally he was here and he would be facing trial. Things are happening the way they should. Once in a while, you read that he wasn’t such a bad guy, but I think that’s denial. Maybe some day, fifty or sixty years down the road, there will be some of that. I can’t really explain it. It’s easier to do it for Dillinger when it was 100 years ago, and there’s no intimacy or immediacy to the harm that they’ve caused.

Q: Fifty or 100 years from now, how do you think people will remember Whitey Bulger?

DL: Well, hopefully as the monster that he was. That’s not to say there won’t be some type of glamorization of him or admiration of his ability to always outfox the cops that were after him, whether it was in Boston or in a different setting when they couldn’t figure out where he was, who he was, or how he was living. It all came to an end, but it came to an end at the age of 81–that’s quite a ride.

In addition to Black Mass, Matt Damon and Ben Affleck have announced plans to film a Whitey Bulger biopic. According to rumor, Jack Nicholson’s character in The Departed was based on Bulger as well.

As is the case with figures like Bulger, there will be (and to an extent, already has been) a storm of media depicting his life and the man he was that will likely color the future’s perception of him. Will his depiction paint him as a murderous, violent psychopath, or a charming Robin Hood figure constantly eluding capture like Frank Abagnale in Catch Me If You Can? Professor Lehr’s book is just one part of the deluge of media that has the power to shape and alter our memory of history.

As the living, breathing Tony Soprano of South Boston awaits trial for 19 murders and a host of other crimes, one can only hope that the man gets his comeuppance. As outlandish and almost surreal as his reign of power and subsequent time as a fugitive seem, to the victims and their families, many of whom still live in the same area, the crimes he committed were very real and their effects linger. We can celebrate and fantasize about these men all we want when we are watching them on the screen, but when they come to life, suddenly the story is much less amusing.

Whitey is available for purchase here.