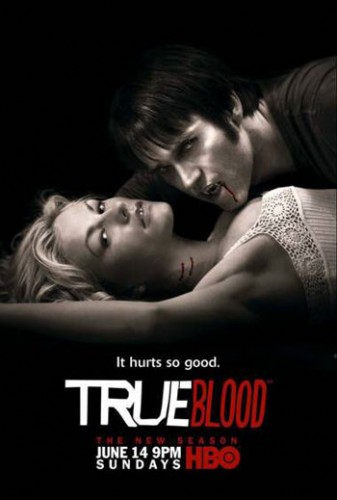

Summer smash hit “True Blood,” which originates from the ‘Southern Vampire Mysteries’ best-seller series by Charlaine Harris, raises the question of what seduces readers to grotesque literature and television, and what the authors behind the fangs are up to.

Grotesque literature is often transposed to television but in the traditional sense it “means something that is alienating or jarring,” said BU English PHD candidate Kristin Bezio. A common way to alienate the reader is to sever the human connection: if the character is not human there cannot be a full empathetic experience. This distance allows the author latitude to portray controversial topics without setting back the reader through offense.

Bezio explains: “In today’s sense of vampires and werewolves, I would say that we still want to feel like we’re on the ‘right’ side of things. I also think that what we’re seeing in these paranormal TV shows and books is a movement toward attempting to literally demonize (vampires are a form of demon, technically) our fears – whether fears of ethnic or cultural Others, or fears of something out of our control. We want to put them in physical form so that we can interact with them on a concrete rather than abstract level.”

Demonizing characters allows people to enact their moral battles in person, rather than on a metaphysical level. In HBO’s version of ‘True Blood,’ vampire marriage is only legal in Vermont. The show portrays vampires’ struggle against political persecution in their pursuit of human freedoms. The persecution against vampire rights on TV parallels that of gay rights in reality: both reveal the appalling nature of humanity

Paranormal characters provide both an emotional distance and yet a physical closeness: “It allows us to distance ourselves from the fundamental discussion going on in the work–vampires aren’t real (in 21st century understanding), and therefore they are a good way of working out our concerns. Real things are harder for our psyches to interpret because they are fraught with all sorts of real-life complications and consequences,” said Bezio. People are better able to work through controversial topics once they are removed from the context of reality and therefore, remove themselves from the beam of blame. Authors recognize this weakness and seize the trope of the grotesque to convey not only a theme, but the monstrous beholder behind it.

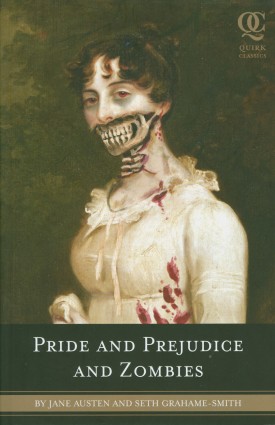

The recent trend in grotesque works has even spread to include perverted revisions to classic British literature. Books like ‘Pride and Prejudice and Zombies,’ by Jane Austen and Seth Grahame-Smith feature zombies that wander the English countryside, which adds the aspect of violence to this classic love story. Proper English women bulk up through martial arts and muskets to battle the sea of undead that storm Britain’s idyllic hillside estates. In the end, Elizabeth does not just accept Darcy’s proposal: she instigates a vicious fight with him in defense of her wronged sister. Nothing shows family love quite like a zombie invasion. As of two weeks ago, a recent addition to the grotesque collection includes ‘Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters,’ by Jane Austen and Ben H. Winters.

Despite the recent surge, people have been dabbling with demons for a long time.

“A desire to understand Otherness, or to demonize it, is fundamental to human nature. After all, Shakespeare’s two characters in ‘The Tempest’ who aren’t human are both “good” and “bad”–the sympathetic Other, Ariel, and the evil Other, Caliban,” explained Bezio. She raises an important point, the history of literature reflects both authors’ use of the grotesque and readers’ predilection towards it.

BU English Professor Magdalena Ostas elaborated on the literary history of the grotesque and its author’s intentions: “I think of Mary Shelley’s novel “Frankenstein” as being as much about the history of science and our conceptions of the human as a novel of ideas. One has to remember that Mary Shelley’s parents (Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin), whom she read intensely, were important figures in the political debates of the 1790s, and one can see in her novel an allegorical engagement with the questions that politically defined that generation.” Ostas suggests that Shelley’s stitched up stiff, Frankenstein, offers her readers both a glimpse into the scientific themes coupled with political stances.

The grotesque even traverses media. In the early 1800’s Spanish painter Francisco Goya unveiled ‘The Black Paintings,’ a collection that contains distorted human and subhuman figures. The ‘El Aquelarre’ installment features a group of disfigured witches closing in on the devil. Faces reveal fear, curiosity, and disgust, all familiar expressions surrounding the current vampire and zombie trend.

“We always try to do one or both to the things we view as different from ourselves. It’s an eternal conflict within human nature,” reflected Bezio. Either way, readers’ and viewers’ widespread obsession with the macabre implies a familiarity in themselves or maybe just an addiction to blood. They read and watch it for some of the same human faults that authors try to express as grotesque: sex, racism, and discrimination.

Aside from fascinating fangs and ravishing leather outfits it turns out that vampires are, in fact, deeper than their eternal skin.