First and foremost, some mild spoilers on Breaking Bad follow.

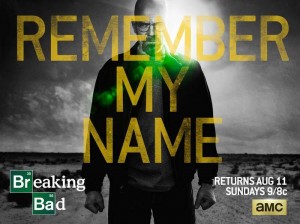

With the episode “Felina,” Breaking Bad finally comes to a close after months of deafening online buzz and years of critical acclaim. Who would’ve thought that a show that started out so modestly would command the kind of attention it does now? In the back half of its fifth and final season, Breaking Bad has repeatedly broken its own ratings records and is only gaining popularity as it goes. Though it’s no Walking Dead in terms of ratings, Breaking Bad has certainly grown into a show that has mass appeal, regardless of its subject matter and its past as a little-watched critical darling.

Breaking Bad follows a line of shows featuring protagonists who lead less than moral lives. In recent years, the term “antihero” has come to be a main buzz word of popular TV programming. Antiheroes can be traced back very far in narrative storytelling, but for most, the beginning of the TV trend can be traced to The Sopranos. Since then, the general consensus on “good television” has tended to skew toward shows featuring antiheroic characters. The question is whether or not this trend will continue or if we’re moving away from stories of men doing bad things for supposedly good reasons.

So what exactly is an antihero? The concept has evolved over time. The traditional definition is that an antihero is a character who has no heroic virtues or qualities whatsoever. This character who bears no resemblance to a traditional hero is nonetheless the protagonist, and either he/she commands our loathing or our understanding. But television, more than any other medium, is about pleasing people. It’s about making something that will make the viewer want to come back next week. And a purely antiheroic character likely won’t accomplish that, so the definition changed. The modern conception of an antihero is more likely a character whose actions lack any semblance of heroic virtue, but whose justifications (however illegitimate) usually embody some type of virtue. It’s a more complex version of the traditional antihero that’s designed to work on a week to week basis.

Though the show definitely fell off in quality in its later years (and featured one of the worst series finales ever), Dexter exemplified the modern antihero drama. Dexter Morgan was a hardwired bad guy, addicted to the thrill of killing even though it made life dangerous for him and his family. His psychopathy was the hook for the show, but what really made people stay (at least initially), was Dexter’s steadfast commitment to his moral code and to his family. He killed only those who were killers themselves (again, this was at first). His actions were always unsavory but his code kept them in check. Who can’t relate to his struggle to suppress his vices because of his dedication to family? He justified his actions with a code, a virtue of the modern antihero.

Kimberly Costello, a TV writing professor at BU and a producer for such shows as Melrose Place and Gilmore Girls (on which she served as co-executive producer), has some ideas on why antiheroes appeal to modern audiences: “For me, we connect more with the antihero. That connection is what generates sales in TV, film, books…If a team wins every game we get bored after a while. Where’s the thrill?” Costello makes a great point here. We live vicariously through the characters we follow and we want that vicarious living to be as emotionally textured as our own lives. Maybe audiences got bored with the narrow range of ways we can relate to conventional heroes. Everybody’s been to a movie and been bored by predictable plot points of the hero saving the day and getting the girl etc. Now we can watch someone make mistakes, try to justify their actions even when they can’t, alienate the people close to them despite their wishes, and feel genuine regret for it. To shorten all this, we’re responding to characters that are closer approximations of ourselves.

So how does Walter White fit into this mold? Can he be considered an extension of this modern antihero? Is he a bad man with good justifications or a good man who makes bad choices? To take it further, could Walt be considered some kind of tragic hero? These questions are slippery ones considering how textured the character is and how magnetic Bryan Cranston’s lead performance is. He’s an inherently likable actor. For my money, if any other actor had played Walter White, this debate wouldn’t be so difficult.

On the one hand, when we first meet Walter White, his tragic circumstances seem to push him into his life of crime. Costello makes a point of saying that Walter doesn’t quite fit the mold of the traditional antihero: “Walter White’s choice to do something bad (make meth) for the greater good (paying medical bills, leaving a financial nestegg [sic]) is in keeping with nearly every protagonist I’ve seen or read. At his core, his incognizant persona, Walter White is a good man. For that reason, I’m not sure ‘antihero’ applies.” Costello’s word choice is important here. Walter White’s incognizant persona, his latent personality from which he justifies his actions, is what carries goodness. His cognizant persona (AKA Heisenberg), the one that is motivated by pride and hubris, the one that carries out actions of unthinkable cruelty, is what pushes against that goodness and provides the central tension of the show. Costello’s point is that Breaking Bad features a traditionally flawed protagonist, not really an antihero. She’s spot on that Walter White certainly doesn’t fit the mold of the traditional antihero, but I’d argue he fits into more neatly in its modernized form. Walter is a kind of tragic antihero, a man who justifies his bad actions with good intentions, but is ultimately brought down by his tragic flaw: pride. This seems to fit in with the characterizations of other TV antiheroes (Boyd Crowder from Justified comes to mind, among others).

But is there anything else that sets Breaking Bad apart from the antihero conventions? I’d argue there is, but it doesn’t really lie with the characterization of Walter White. What I’d argue does separate Breaking Bad from the pack is the show’s treatment of Walter White. No antihero show I’ve seen has put their central character through the ringer like Breaking Bad has to Walter White (or, in parallel, Jesse Pinkman) in its final season. Without going into too much detail, Vince Gilligan and co. have done everything they can this season to show that Walter’s justifications have all been for nothing. He broke bad way back in the first season and it’s all been a slippery slope since then. No matter how many times Walter said what he was doing was for his family, it was to some extent really motivated by his pride. At a certain point, his actions outweigh his justifications. We can no longer make the separation between his cognizant and incognizant selves. They can no longer be compartmentalized. They inform each other. He’s always been Walter White and he’s always been Heisenberg. Lesser shows (like Dexter) are content to leave their respective protagonists off the hook without really examining the consequences of their actions. Breaking Bad is so brutal and so good precisely because it shows the awful repercussions of Walt’s actions in excruciating detail. Not only for Walt, but for everyone who’s been involved with him personally and professionally.

Breaking Bad’s universe is a decidedly moral one. Though it may have taken a while, what goes around eventually comes around. We can only have fun watching the badass that is Heisenberg for so long before he actually destroys everything he thought he stood for. Is this a sign of the antihero drama maturing in a way? Instead of watching characters whose faulty morals we relate to, now we’re seeing the actual consequences of those faulty morals. Walter’s ego is inextricably linked to his conception of caring for his family; it’s a deadly combination that creates nothing but chaos and violence-and all supposedly in the name of family. Breaking Bad is almost like an old school morality tale in that way. It plays on the conventions of popular antiheroic narratives by building up the stature of its protagonist higher and higher only to blow it all up like it inevitably would. There’s an element of classic tragedy at play that tempers the standard antihero elements of the show.

What this means for the future of “good TV” remains to be seen. No medium is more unpredictable right now. Not only is content changing, but distribution is too; Netflix was nominated for and won Emmys this year. But what’s clear is that TV’s most popular conventions are changing. TV has always been and will continue to be a manifestation of public consciousness. We watch things because we relate to them, and what shows are popular do say something about the viewing public. Costello puts it this way: “As to the modern audience, I believe it’s a result of timing. While bad things happened in the world during the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s, not many critically negative or violent things happened in America…Our TV heroes were good cops nabbing bad people, good doctors saving lives, and good lawyers fighting to protect the rights of victims.” Costello goes on to argue that after the events of 9/11, the viewing consciousness completely changed and our heroes changed with it. Our sociopolitical climate has a real effect on what we watch and what we hold up as good art. As it stands now, bad men doing bad things for good reasons and getting away with it are no longer an accurate reflection of modern audiences. Where TV writing is going is hard to predict, but with the departure of Breaking Bad, it seems that antiheroes as we know them might be on their way out.

For a similar and very well-written article, take a look at this piece from The AV Club: http://www.avclub.com/articles/breaking-bad-ended-the-antihero-genre-by-introduci,103483/?utm_source=Twitter&utm_medium=SocialMarketing&utm_campaign=Default:1:Default